Resources

Fencing By Remote Control

By Gail Damerow

(Printed in Backyard Poultry Magazine)

The pasture where our laying hens forage is surrounded by a smooth-wire electric fence that's designed more to keep predators out than to keep the chickens in. During the day the hens freely duck through the fence to forage in our orchard. That's okay, because we have no near neighbors for them to bother, and during the morning and evening when most predators are prowling, the chickens are safely back behind the electric fence.

Sometimes our chickens share their pasture with our dairy goats. Then we put up electric poultry netting, not so much to keep the chickens in, but to keep the baby goats from getting into the coop to eat the lay ration, and to keep the mama goats from dismantling the chickens' automatic door closer.

If you have any kind of electric fence, you know something is always going wrong. A storm blows debris all over the fence causing a short circuit. Rain softens the soil, loosening the fiberglass net posts so the net rests against wet ground–another short. Deer blast through the fence and break a wire–you guessed it, another short.

So we are constantly on the lookout for problems that need fixing, which typically involves trotting back and forth along the fenceline to find faults, turn off the energizer, fix the problem, turn the energizer back on, check to see that the problem is truly fixed, then move on to find the next problem. On a humid Tennessee day with the temperature pushing 100 degrees, all that walking gets exhausting. Someone at Kencove Farm Fence Supplies must have been just as tired as we were of walking up and down fencelines, and was clever enough to design an energizer you can turn off and back on by remote-control. How cool is that?!

Setting Up the System

Energizer, fence charger, fencer, fence controller, power unit–all these terms refer to that little box responsible for the big jolt you get if you touch an electric fence. It works by converting household electricity or battery-stored power into higher voltage, then sending the current through fence wires in steady, short bursts. You can hear the energizer's slow click-click-click as it sends out the pulses.

To work properly, an energizer needs a good grounding system, which is accomplished by connecting the energizer's ground terminals to at least three ground rods spaced 10 feet apart. Under normal circumstances, a fence's hot wires are insulated from the earth and the circuit is open. To generate a shock, current must flow from the energizer through the hot wires and back to the energizer through the soil.

To work properly, an energizer needs a good grounding system, which is accomplished by connecting the energizer's ground terminals to at least three ground rods spaced 10 feet apart. Under normal circumstances, a fence's hot wires are insulated from the earth and the circuit is open. To generate a shock, current must flow from the energizer through the hot wires and back to the energizer through the soil.When the circuit is completed by current flowing through the feet of an animal standing on the ground, the system is called a ground-return or earth-return system. With this system, all horizontal wires are energized. This system works fine for a relatively short fence in an area of even rainfall, where the soil remains conductive and serious predators such as coyotes and bobcats are not a problem.

An earth-return system doesn't work well when the ground is not adequately conductive. Such a condition occurs when the soil is extremely dry, sandy, rocky, or frozen. An earth-return system also doesn't work well for animals that jump between wires; they won't get a shock because their feet are off the ground. In such situations, a wire-return system is more effective than an earth-return system. A wire-return system is less dependent on soil conditions. It deters animals having built-in insulation and those performing tricky maneuvers like slipping between wires instead of crawling under the fence or climbing over it. And, unlike the earth-return system, a wire-return system works well even for long fences.

In a wire-return system, not all the fence wires are energized, or hot; some of them are grounded. In this type of fence, the hot wires are said to be positive while the grounded wires are said to be negative. Our perimeter smooth-wire fence, for instance, has six wires that, from the bottom up, are: positive-positive-negative-positive-negative-positive.

When earth-return or wire-return, a smooth wire fence generally will not keep chickens confined. Their feet are too small to provide much conductivity and their feathers provide terrific insulation against shock. For this reason,electric poultry netting is popularly used to keep chickens in.

Electric poultry netting is designed so you can energize it either as a ground-return or a wire-return system. Every other wire of our Kencove net fence, for instance, is orange and all the orange wires are bundled together; the alternating wires are green and are similarly bundled together. For a ground-return system, both bundles are connected to the energizer's power terminal. For a wire-return system, which is preferable for chickens, the orange bundle is connected to the energizer's power terminal and the green bundle is connected to the ground terminal.

When a wire-return fence is more than 1,000 feet long, extra grounding rods are needed, each connected to all the fence's ground wires. For a long fence where the soil is reasonably moist, the rods may be spaced every 3,000 to 5,000 feet. For a short fence and/or where soil conditions are dry, rods should be spaced every 1,000 to 1,500 feet. Evenly spacing the rods isn't as important as putting them in low spots where the soil stays moist (where the grass is greenest).

Shorts and Leaks

Shorts and Leaks

Whether your fence is ground return or wire return, it's important to make sure the hot wires have no contact with the ground or the grounding system. A direct connection would, of course, result in a dead short. Lesser contacts, called shorts or leaks, drain energy from the fence, making a plug-in system less effective and drawing down a battery-operated system more rapidly.

Energy leaks have any number of causes: grass or weeds growing against hot wires or windblown twigs or branches lying across them; cracked insulators; bugs, leaves, or dust lodged in insulators; salty sea air; a broken wire. A common problem with net fencing is that the posts are so far apart the bottom sags, causing the lowest hot wire to lie directly on the ground. Most of these situations result in arcing pulses of current that, instead of flowing smoothly from one place to another jump across a narrow gap by means of a spark.

When arcing occurs, you can usually hear the snap of the jumping spark, which can help you find and correct the source of leakage. Whenever you check your electric fence, listen for problems as well as look for them. If the source of snapping sounds eludes you, go back at night and you'll actually see sparks fly.

The remote-control energizer helps you detect shorts by means of its unique built-in diagnostic indicator. A ground condition indicator light warns when the ground terminals exceed 1,000 volts telling you it's time to pour water on dry ground rods. A voltage indicator light warns when the voltage drops below 3,500 volts telling you to look for (and fix!) whatever is causing the short.

Finding Faults

Finding Faults

When a fence demands attention, a hand-held fence tester is indispensable for finding the problem. The fence testers we've used in the past had two terminals, one on the unit itself and another connected to the unit by a length of wire. The first terminal is attached to a hot wire, the other to some part of the ground system. With both terminals in place, the tester indicates how much voltage is getting through.

I can't recall how many fence testers we've bought over the years. Some had delicate terminals that broke easily and needed constant repair until they became unrepairable. Others had such a poor display you couldn't read it on a sunny day, and they ended up in the trash. Using any of them involved walking down the fenceline looking for problems, then walking back to the energizer to turn off the juice, walking back to fix the problem, walking back to turn on the fence, walking back to check the repair, walking, walking, walking.

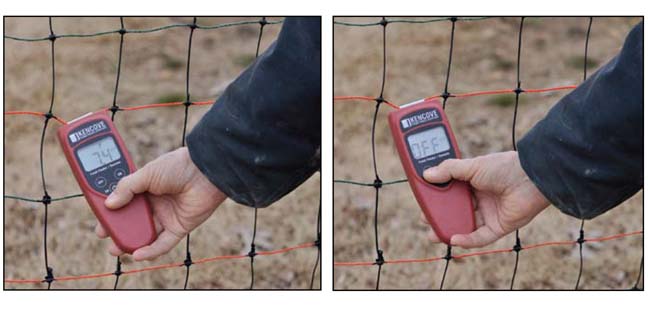

Kencove's combination remote-control and fence tester that works with the remote-ready energizer is sturdier and easier to read than any I've seen so far. The top of the remote has a metal hook that, when pressed against a hot wire, reads information about the voltage, amount of current flow, and direction of current flow on a nice big display.

I'm of the mind that nearly anything can be improved, and in this case I find the fence hook to be a tad short, causing it to slide off the wire unless you're careful to hold it steady. And I believe this nice remote should be kept in a pouch to prevent the display from getting scratched when the unit is tossed in a glove compartment or tool box. Luckily we happen to have an unused amp meter pouch with a belt loop that perfectly fits the remote.

And now we come to the truly exciting part of our new system: using the remote control to turn off the energizer without taking a step. When you find a problem and want to turn off the current to fix it, you hook the controller over a hot wire and press the "off" button; you know the fence is off because the display tells you so. After making a repair, you hook the controller over any hot wire and press the "on" button; you know the fence is on because the display reads the voltage and current. It's that simple!

The manual says it works on any kind of electric fence metal, poly wire, ribbon, braid, or net. Skeptics that we are, the first time we used the remote on our perimeter fence, one of us walked all the way around to the energizer to make sure it was really and truly off. Yup, it was. Skeptics that we are, we didn't believe the remote would work as well on the poly twine net fence. So the first time we tried it, one of us walked to the energizer to make sure it was off. Yup, it was!

Still, after decades of walking back and forth troubleshooting fences, I'm almost embarrassed to tell you how many times, out of habit, we have walked to the energizer to turn it off while carrying the remote control. But at last it's sinking in: No longer need we walk our legs off while troubleshooting our electric fences!

Photos courtesy of Gail Damerow. Gail Damerow is the author of Fences for Pasture & Garden, along with her many fine books about raising chickens. Her books are available from the Backyard Poultry bookstore at www.backyardpoultrymag.com.